Afghan economic growth fell by more than 10 percentage points in 2013, down to 3.1 percent from 14.4 percent a year earlier. This dramatic decline marks the bursting of an economic bubble that had been inflated by a decade of extraordinarily high security spending and foreign aid, now winding down with the withdrawal of NATO forces in 2014.

The slowdown in aggregate economic performance was exacerbated by high-profile terrorist attacks in the heart of Kabul, political uncertainty surrounding the April 2014 presidential election, and disagreements among key allies concerning negotiations with the Taliban. Collectively, these factors clouded the economic outlook and depressed private sector expectations.

The impact of the decline in foreign aid is being felt unevenly across the country. Because of the choices made by donors, and the predominant role of stabilisation and military spending, the conflict-affected provinces have had significantly higher per capita aid than the more peaceful (and often poorer) provinces. As a result, the slowdown in aid has begun to be felt more acutely in the conflict-affected areas and in urban centres, which have lost jobs as military bases and provincial reconstruction teams close. In urban centres, such as Kabul, wage levels of higher-qualified people are declining due to fewer opportunities in donor-financed projects.

In a major blow to Afghan hopes for high and sustainable economic growth, security concerns have prompted Chinese investors to demand a review of a landmark $3 billion dollar contract to produce copper at Aynak. A smaller but symbolically important oil project in northern Afghanistan has also ground to a halt, raising doubts as to whether Afghanistan can realise the ‘Silk Road’ scenario of high and sustainable growth driven by exploitation of its considerable wealth of natural resources.

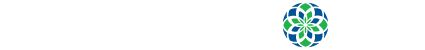

The Afghan economy remains highly dollar-dependent, making the dollar exchange rate of the Afghani an important barometer of private sector expectations. The Afghani continued its downward trend in 2013, depreciating by 11.25 percent against the dollar as the economy slowed and political uncertainty fuelled capital flight. A weakening currency makes imports more expensive and should boost exports, leading to a narrowing of the trade deficit. However, we observed the opposite in 2013, with the trade deficit widening to $8.3 billion from $6.0 billion in 2012.

The lack of a positive export response to the exchange rate depreciation is worrisome because it underscores the fact that Afghanistan’s export base has relatively few tradable products and these are heavily concentrated in a few markets. Dry fruits, which account for around one-third of official exports, declined by 21 percent, and carpet exports, another major item, nearly halved to $23 million. The strong depreciation of the Pakistani rupee against the US dollar may have accounted for lower demand for Afghan carpets. Pakistan is traditionally the most important market for Afghan carpets, where they are processed and exported to European markets. The declining trend in dry fruits exports, however, seems to indicate a loss of competiveness in important EU markets.

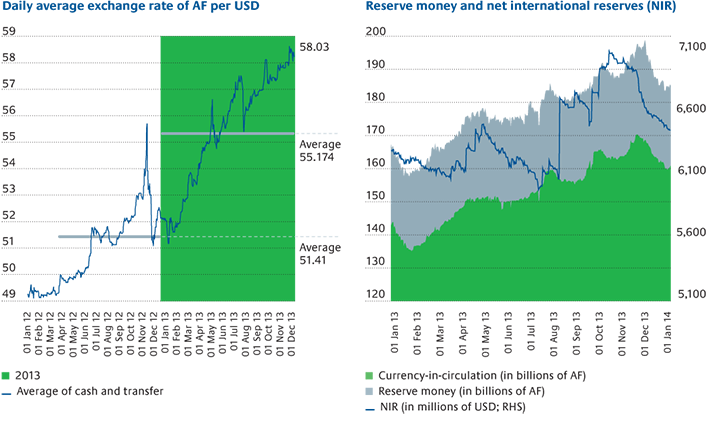

The amount of foreign reserves (net international reserves) held by the Central Bank is a key indicator of financial stability because it marks the country’s ability to withstand capital flight. Foreign reserves stood at $6.9 billion at the beginning of December, 2013, slightly above the $6.2 billion considered sufficient to buffer any negative shocks. The demand for money, measured by the level of reserve money, was weak in 2013 reflecting the slowing economy.

Systemic risk in the banking sector is a major concern in Afghanistan where a shock to an important bank can pose risks to otherwise sound banks. In that respect, the Afghan banking sector appears to be recovering slowly from the Kabul Bank crisis of 2010. Sector profits grew to AF 649 million in 2013, up from a loss of AF 1.71 billion in 2012. This was reflected in a slight improvement in return on assets to 0.30 percent, up from -0.99 percent in 2012.

Loans and deposits in the banking system also showed marked improvement with total gross loans increasing by 19.34 percent and deposits by 9.96 percent to AF 207.30 billion. The banking system as a whole was adequately capitalised, although a few problem banks were undercapitalised or only marginally so. One state-owned bank that has a capital adequacy ratio of less than 12 percent was given forbearance from the central bank until it is privatised, while two other banks have capital adequacy ratios close to the minimum threshold (12 percent of risk weighted assets).

The banking industry faces four pressing challenges:

- How to maintain double-digit returns on equity as adverse factors threaten profitability? The business landscape has changed and in the foreseeable future there will be a fundamentally lower ROE environment. This will be driven by a combination of revenue compression and changing capital and liquidity requirements as the central bank moves to strengthen the ability of banks to withstand periods of market stress, mounting cost pressures from critically needed investments (such as IT), and an increase in the costs of doing business in Afghanistan (heightened security spending).

- What kind of new products and sources of revenues are needed for retail and corporate clients in an environment of slow private-sector growth and heightened risk?

- How to grow a banking system hampered by the lack of high-quality and experienced staff to manage customer-facing units and the back office?

- How to attract and maintain quality customers as competition intensifies through willingness to reduce returns?

The fragile security environment has been the single most binding constraint to private-sector investment and private-sector-led growth. Prospects for the economy will therefore depend on Afghanistan’s success in achieving peace, stability, and reconciliation and how banks respond to the changing business environment.